Vilnius, August 4

I am enjoying a second day off here in lovely Vilnius, resting my weary thighs and drinking in the gorgeous sights of this beautiful Baroque old town. I have a couple of blog updates to do today, on quite different themes, so here goes the first one.

I rode here from Lvov, now in the Ukraine, over the course of seven long days in the saddle. I rode through modern-day Ukraine, Poland, Belarus and Lithuania, but if this ride had been done in 1938, I would have spent the entire ride in one country, pre-WWII Poland. As such, this whole area was devastated during the war by both Nazi Germany and the USSR of Stalin. The group worst affected was, of course, the Jews of eastern Europe, most of whom were concentrated in what was then Poland. The road I followed from Lvov to Vilnius was a true Trail of Tears; like

the removal of the Cherokee in the Southeast of the US in the 1830s, this was the road followed by hundreds of thousands of European Jews in forced relocations designed to destroy their culture and remove them from the landscape. Although I had planned my route to visit the sites of Belzec and Sobibor, I hadn't really thought about the entire route, running parallel to train lines, as the actual route of deportations. This realization grew on me as I rode, colouring my perception of this area, called by historian Timothy Snyder

"The Bloodlands" in an outstanding historical book of the same title.

It started as I rode out of Lvov. On the way out of town, as I passed under the train tracks towards Lublin, I saw a moving memorial to the deportation of Jews from Lvov. Lvov had almost 150,000 Jewish citizens in 1941; almost all of them were sent to Belzec extermination site, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews living in smaller towns around Lvov (the province of Galicia). The statue, of a robed, prophetic man raising his arms to heaven, stood beside plaques saying that this was the start of a road to death and destruction for the Jews of Galicia. I rode out of town, realizing that my road lay almost parallel to the train tracks which would have carried trainload after trainload of victims to Belzec.

After crossing the border (for once, it was painless), it was a short 15 kilometres to the tiny town of Belzec, only 85 km from the great metropolis of Lvov. There, just across the train tracks, was the memorial I had come to see. Most Westerners, if asked about the Holocaust, can come up with the names of Auschwitz and Dachau, but far fewer know the name of Belzec. And yet, in some sense, it was

Belzec, along with

Sobibor and

Treblinka, that were the very heart, the epicentre of evil, of Hitler's Holocaust. At the

Wannsee Conference in early 1942, chaired by

Reinhard Heydrich, the decision was made to kill all the Jews in the General Government of Poland (most of the Polish territories captured in 1939). The Jews further east, in the parts of Poland captured by the Soviets in 1939 as well as Soviet Lithuania, Belarus and Poland, were killed in large numbers in 1941, but those in the General Government were still alive, herded into ghettoes and exploited as slave labour. After Heydrich's murder in May, 1942 in Prague, the operation to kill Poland's Jews was named Operation Reinhard in his honour. Belzec was the first of three extermination camps constructed for this purpose, and it operated from late March to December of 1942. In that time, nearly 500,000 Jews were murdered here, and only 2 were known to have escaped. Perhaps it's this grisly efficiency that has kept Belzec out of the public eye; there was nobody left to tell the story.

There's also nothing left to see. Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, which were captured more or less intact and functioning, Belzec (and its sister facilities at Sobibor and Treblinka) had long since served its hideous purpose. After the last murders in December, 1942, the site was completely dismantled. In 1943 a group of Jewish slave labourers was brought in to dig up the bodies and completely burn them. The ashes were then reburied, the site was planted with trees and the labourers were sent to their deaths at Sobibor. It was as though this site of immense evil, along with the hundreds of thousands of victims, had never existed. To this day, Galicia has almost no Jewish inhabitants; Hitler's mad dream came true, and few of the handful of survivors remained. Galicia, once a vibrant mix of Polish Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox believers, Jews, Roma, Germans and Armenians, has been simplified by Hitler, and subsequent post-WWII ethnic resettlements, into an almost entirely Ukrainian area. The fact that so few people know today about Belzec only adds to the sense that Hitler's attempts to cover up the crimes have succeeded to a large degree.

With nothing visible to look at, a huge artificial memorial was established in 2004. A large field of volcanic rock has been created, ringed by tangled steel rebar and the names of cities whose Jewish inhabitants rode the rails to Belzec. A few railway sleepers and rails have been dug up; they were probably used as pyres during the 1943 coverup operation. A passage leads gradually underground through the rocks to a huge stone face inscribed with an inscription from the Book of Job: "Earth, do not cover my blood. Let there be no resting place for my outcry!" in Polish, English and Hebrew. I found it very moving in its minimalism. An underground museum has also been built, very simple and compelling in its exhibits and information. You can easily read all the captions and information panels in under an hour, but it will stay in your memory for life.

I pedalled away towards Zamosc and its Renaissance core, where a wonderful Renaissance synagogue now stands empty; there are no Jewish citizens of Zamosc anymore. I went to bed very pensive, pondering the ghosts of history.

The next day was more of the same. I rode a long day through the gently rolling farmland of eastern Poland, through the city of Chelm, towards the point where the modern borders of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine meet. All the way, there was a train line somewhere close to the road, and again it was a silent witness to the horrors of the 1940s. I passed through Izbica, which was mentioned in the Belzec museum as a

concentration camp that served as a feeder to the death factories of Sobibor and Belzec. This time no memorial plaque or sign was in evidence. I pedalled north into a pretty area of flat forest and small lakes, much beloved of fishermen and local Polish tourists on bicycles. The Dutch province of Gelderland (where my father hails from, originally) has helped the Polish government set up a network of bike trails to explore this area.

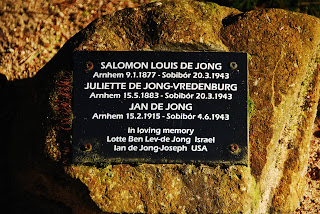

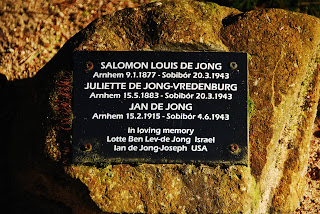

In the centre of the forest, straddling (naturally) a railway line, lies Sobibor death camp. This time, as I had already ridden 115 km, it was too late to get into the museum, but the open-air site was still open. Again, there are no physical remains of the facility; the Nazis obliterated it in 1943 as well. The memorials here are much simpler, but in some ways more moving and more disturbing. The trees planted in 1943 have grown up into a magnificent forest. Although I generally love forests, the evil done in this place lends a malevolent air to the trees. Along one path in the forest, a series of memorial stones have been laid to commemorate individuals known to have died in Sobibor.

Although the vast majority of victims were Polish Jews, there were also some victims brought in from the Netherlands, France and Germany. I found it strange, and somehow disturbing, that the memorial stones were almost all for the Dutch victims, often laid by the descendants of the deceased. Some came from Arnhem, close to where my father grew up. Others had the same first name as my father, Gerrit. These coincidences, by creating a feeling of a linkI wondered whether it was partly because so many Dutch Jews managed to survive the war to remember their dead relatives; perhaps there were so few stones for Polish victims because so few of them had any surviving descendants to come lay stones for them. Or perhaps the post-WWII historical narrative of the Soviet bloc, in which Soviet, and especially Russian, victims of the Nazis were paramount, left little time or inclination to consider the Jewish victims of the Nazis. I don't know, but something about it left me feeling uneasy.

As I took photographs of the overgrown, unused railway siding that once led to the camp, a busload of young Israelis, some wrapped in the Israeli flag, came out of the site singing. They seemed to be on a Holocaust memorial tour, and it must have been even more emotional for them than for me to see this site of mass death, in which an estimated 250,000 people were killed. Sobibor is also little known in the West, again partly perhaps it was so deadly efficient; only about 50 people are known to have survived, most of whom escaped in the prisoner revolt in October 1943 that damaged the facility and led to it being closed.

By pure coincidence, a few days earlier I had stayed in a hotel with satellite TV and had watched a History Channel documentary about Simon Wiesenthal. One of his most notable successes in tracking down war criminals was his location of the commander of Sobibor (and later Treblinka), Franz Stangl, in Sao Paolo in 1967. Stangl was arrested, extradited to West Germany and tried for war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison, which amounted to six months, as he died of a heart attack in 1970. Much of what we know about Sobibor came to light during this trial.

It was a shock, after all this grim recollection of death and destruction, to ride 10 kilometres through the forbidding forest and emerge at a lake south of Wlodawa (Okuninka) where thousands of people were enjoying a summer afternoon at the lake. Restaurants, fun fairs, bars and shops were packed. Life moves on, even at the site of profound tragedy.

The ride through Belarus, still along the rail lines of pre-WWII Poland, had fewer overt reminders of the Holocaust, although plenty of WWII. Belarus bore the brunt of fighting on the Eastern Front, with around a third of its population dying between 1941 and 1944. There are memorials everywhere to the Red Army, still faithfully tended with fresh wreaths, and memorials to the partisans who fought the Germans from the forests. However, the Jews of modern-day western Belarus (which was part of Poland occupied by the Russians) suffered horribly in the war years, most of them summarily executed in 1941, immediately after the German invasion, shot in forests and buried in mass graves by the SS and locally recruited death squads.

Arriving here in Vilnius, dubbed the Jerusalem of the North by Napoleon, there are more remembrances of the Holocaust. Vilnius had 140,000 Jewish citizens in 1940, and there were some 200,000 in the country as a whole. Fewer than 10,000 would survive the war. I went to the Lithuanian national holocaust memorial museum, a moving tribute to the destruction of an entire community and way of life. On my way out of town tomorrow, riding toward the coast, I will pass Pareniai, where so many Vilnius Jews were executed in pits dug outside the city.

This section of the bike trip has taught me a lot I didn't know about what happened in WWII in eastern Europe, something that is often passed over lightly in our Western history books. It has also left me saddened, thinking of how often this sort of wholesale destruction of a people has been attempted over the centuries (the North American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, Rwanda's Tutsis, the Armenians of eastern Anatolia, entire city-states in Central Asia during the Mongol onslaught, to name but a few cases). I wonder whether, as Earth's population continues to skyrocket and as more and more people aspire to a Western standard of living, putting increasing strains on land, water, food, forests, oceans, whether we will see a resurgence of this sort of lebensraum idea and killing and mass deportation to achieve it. Today war criminals get sent to the Hague; perhaps in 50 years they will be given medals by their countries instead.

Postscript, Kaunas, August 7

On my way out of Vilnius two days ago, I stopped in the forest of Paneriai, the principal site of executions of Lithuanian Jews from 1941 to 1944. As in much of the territory conquered by the Germans in 1941, from the very first days of the invasion, there were mass killings of local Jewish citizens. At first, the Germans stirred up local nationalists, angered by 2 years of Soviet oppression, by equating Jews to the hated Communists, and there were a number of unorganized killings by Lithuanian militias. Quite soon, however, the Germans organized matters and had the Lithuanian police battalions carry out their dirty work. Nearly 100,000 people were murdered in Paneriai, and most of them were subsequently dug up, burned and then the ashes reburied. I had the forest to myself in the early morning, and walking around the various Soviet and post-Soviet memorials was very moving.

It started as I rode out of Lvov. On the way out of town, as I passed under the train tracks towards Lublin, I saw a moving memorial to the deportation of Jews from Lvov. Lvov had almost 150,000 Jewish citizens in 1941; almost all of them were sent to Belzec extermination site, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews living in smaller towns around Lvov (the province of Galicia). The statue, of a robed, prophetic man raising his arms to heaven, stood beside plaques saying that this was the start of a road to death and destruction for the Jews of Galicia. I rode out of town, realizing that my road lay almost parallel to the train tracks which would have carried trainload after trainload of victims to Belzec.

It started as I rode out of Lvov. On the way out of town, as I passed under the train tracks towards Lublin, I saw a moving memorial to the deportation of Jews from Lvov. Lvov had almost 150,000 Jewish citizens in 1941; almost all of them were sent to Belzec extermination site, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews living in smaller towns around Lvov (the province of Galicia). The statue, of a robed, prophetic man raising his arms to heaven, stood beside plaques saying that this was the start of a road to death and destruction for the Jews of Galicia. I rode out of town, realizing that my road lay almost parallel to the train tracks which would have carried trainload after trainload of victims to Belzec.

After crossing the border (for once, it was painless), it was a short 15 kilometres to the tiny town of Belzec, only 85 km from the great metropolis of Lvov. There, just across the train tracks, was the memorial I had come to see. Most Westerners, if asked about the Holocaust, can come up with the names of Auschwitz and Dachau, but far fewer know the name of Belzec. And yet, in some sense, it was Belzec, along with Sobibor and Treblinka, that were the very heart, the epicentre of evil, of Hitler's Holocaust. At the Wannsee Conference in early 1942, chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, the decision was made to kill all the Jews in the General Government of Poland (most of the Polish territories captured in 1939). The Jews further east, in the parts of Poland captured by the Soviets in 1939 as well as Soviet Lithuania, Belarus and Poland, were killed in large numbers in 1941, but those in the General Government were still alive, herded into ghettoes and exploited as slave labour. After Heydrich's murder in May, 1942 in Prague, the operation to kill Poland's Jews was named Operation Reinhard in his honour. Belzec was the first of three extermination camps constructed for this purpose, and it operated from late March to December of 1942. In that time, nearly 500,000 Jews were murdered here, and only 2 were known to have escaped. Perhaps it's this grisly efficiency that has kept Belzec out of the public eye; there was nobody left to tell the story.

There's also nothing left to see. Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, which were captured more or less intact and functioning, Belzec (and its sister facilities at Sobibor and Treblinka) had long since served its hideous purpose. After the last murders in December, 1942, the site was completely dismantled. In 1943 a group of Jewish slave labourers was brought in to dig up the bodies and completely burn them. The ashes were then reburied, the site was planted with trees and the labourers were sent to their deaths at Sobibor. It was as though this site of immense evil, along with the hundreds of thousands of victims, had never existed. To this day, Galicia has almost no Jewish inhabitants; Hitler's mad dream came true, and few of the handful of survivors remained. Galicia, once a vibrant mix of Polish Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox believers, Jews, Roma, Germans and Armenians, has been simplified by Hitler, and subsequent post-WWII ethnic resettlements, into an almost entirely Ukrainian area. The fact that so few people know today about Belzec only adds to the sense that Hitler's attempts to cover up the crimes have succeeded to a large degree.

After crossing the border (for once, it was painless), it was a short 15 kilometres to the tiny town of Belzec, only 85 km from the great metropolis of Lvov. There, just across the train tracks, was the memorial I had come to see. Most Westerners, if asked about the Holocaust, can come up with the names of Auschwitz and Dachau, but far fewer know the name of Belzec. And yet, in some sense, it was Belzec, along with Sobibor and Treblinka, that were the very heart, the epicentre of evil, of Hitler's Holocaust. At the Wannsee Conference in early 1942, chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, the decision was made to kill all the Jews in the General Government of Poland (most of the Polish territories captured in 1939). The Jews further east, in the parts of Poland captured by the Soviets in 1939 as well as Soviet Lithuania, Belarus and Poland, were killed in large numbers in 1941, but those in the General Government were still alive, herded into ghettoes and exploited as slave labour. After Heydrich's murder in May, 1942 in Prague, the operation to kill Poland's Jews was named Operation Reinhard in his honour. Belzec was the first of three extermination camps constructed for this purpose, and it operated from late March to December of 1942. In that time, nearly 500,000 Jews were murdered here, and only 2 were known to have escaped. Perhaps it's this grisly efficiency that has kept Belzec out of the public eye; there was nobody left to tell the story.

There's also nothing left to see. Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, which were captured more or less intact and functioning, Belzec (and its sister facilities at Sobibor and Treblinka) had long since served its hideous purpose. After the last murders in December, 1942, the site was completely dismantled. In 1943 a group of Jewish slave labourers was brought in to dig up the bodies and completely burn them. The ashes were then reburied, the site was planted with trees and the labourers were sent to their deaths at Sobibor. It was as though this site of immense evil, along with the hundreds of thousands of victims, had never existed. To this day, Galicia has almost no Jewish inhabitants; Hitler's mad dream came true, and few of the handful of survivors remained. Galicia, once a vibrant mix of Polish Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox believers, Jews, Roma, Germans and Armenians, has been simplified by Hitler, and subsequent post-WWII ethnic resettlements, into an almost entirely Ukrainian area. The fact that so few people know today about Belzec only adds to the sense that Hitler's attempts to cover up the crimes have succeeded to a large degree.

With nothing visible to look at, a huge artificial memorial was established in 2004. A large field of volcanic rock has been created, ringed by tangled steel rebar and the names of cities whose Jewish inhabitants rode the rails to Belzec. A few railway sleepers and rails have been dug up; they were probably used as pyres during the 1943 coverup operation. A passage leads gradually underground through the rocks to a huge stone face inscribed with an inscription from the Book of Job: "Earth, do not cover my blood. Let there be no resting place for my outcry!" in Polish, English and Hebrew. I found it very moving in its minimalism. An underground museum has also been built, very simple and compelling in its exhibits and information. You can easily read all the captions and information panels in under an hour, but it will stay in your memory for life.

I pedalled away towards Zamosc and its Renaissance core, where a wonderful Renaissance synagogue now stands empty; there are no Jewish citizens of Zamosc anymore. I went to bed very pensive, pondering the ghosts of history.

The next day was more of the same. I rode a long day through the gently rolling farmland of eastern Poland, through the city of Chelm, towards the point where the modern borders of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine meet. All the way, there was a train line somewhere close to the road, and again it was a silent witness to the horrors of the 1940s. I passed through Izbica, which was mentioned in the Belzec museum as a concentration camp that served as a feeder to the death factories of Sobibor and Belzec. This time no memorial plaque or sign was in evidence. I pedalled north into a pretty area of flat forest and small lakes, much beloved of fishermen and local Polish tourists on bicycles. The Dutch province of Gelderland (where my father hails from, originally) has helped the Polish government set up a network of bike trails to explore this area.

In the centre of the forest, straddling (naturally) a railway line, lies Sobibor death camp. This time, as I had already ridden 115 km, it was too late to get into the museum, but the open-air site was still open. Again, there are no physical remains of the facility; the Nazis obliterated it in 1943 as well. The memorials here are much simpler, but in some ways more moving and more disturbing. The trees planted in 1943 have grown up into a magnificent forest. Although I generally love forests, the evil done in this place lends a malevolent air to the trees. Along one path in the forest, a series of memorial stones have been laid to commemorate individuals known to have died in Sobibor.

With nothing visible to look at, a huge artificial memorial was established in 2004. A large field of volcanic rock has been created, ringed by tangled steel rebar and the names of cities whose Jewish inhabitants rode the rails to Belzec. A few railway sleepers and rails have been dug up; they were probably used as pyres during the 1943 coverup operation. A passage leads gradually underground through the rocks to a huge stone face inscribed with an inscription from the Book of Job: "Earth, do not cover my blood. Let there be no resting place for my outcry!" in Polish, English and Hebrew. I found it very moving in its minimalism. An underground museum has also been built, very simple and compelling in its exhibits and information. You can easily read all the captions and information panels in under an hour, but it will stay in your memory for life.

I pedalled away towards Zamosc and its Renaissance core, where a wonderful Renaissance synagogue now stands empty; there are no Jewish citizens of Zamosc anymore. I went to bed very pensive, pondering the ghosts of history.

The next day was more of the same. I rode a long day through the gently rolling farmland of eastern Poland, through the city of Chelm, towards the point where the modern borders of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine meet. All the way, there was a train line somewhere close to the road, and again it was a silent witness to the horrors of the 1940s. I passed through Izbica, which was mentioned in the Belzec museum as a concentration camp that served as a feeder to the death factories of Sobibor and Belzec. This time no memorial plaque or sign was in evidence. I pedalled north into a pretty area of flat forest and small lakes, much beloved of fishermen and local Polish tourists on bicycles. The Dutch province of Gelderland (where my father hails from, originally) has helped the Polish government set up a network of bike trails to explore this area.

In the centre of the forest, straddling (naturally) a railway line, lies Sobibor death camp. This time, as I had already ridden 115 km, it was too late to get into the museum, but the open-air site was still open. Again, there are no physical remains of the facility; the Nazis obliterated it in 1943 as well. The memorials here are much simpler, but in some ways more moving and more disturbing. The trees planted in 1943 have grown up into a magnificent forest. Although I generally love forests, the evil done in this place lends a malevolent air to the trees. Along one path in the forest, a series of memorial stones have been laid to commemorate individuals known to have died in Sobibor.

Although the vast majority of victims were Polish Jews, there were also some victims brought in from the Netherlands, France and Germany. I found it strange, and somehow disturbing, that the memorial stones were almost all for the Dutch victims, often laid by the descendants of the deceased. Some came from Arnhem, close to where my father grew up. Others had the same first name as my father, Gerrit. These coincidences, by creating a feeling of a linkI wondered whether it was partly because so many Dutch Jews managed to survive the war to remember their dead relatives; perhaps there were so few stones for Polish victims because so few of them had any surviving descendants to come lay stones for them. Or perhaps the post-WWII historical narrative of the Soviet bloc, in which Soviet, and especially Russian, victims of the Nazis were paramount, left little time or inclination to consider the Jewish victims of the Nazis. I don't know, but something about it left me feeling uneasy.

Although the vast majority of victims were Polish Jews, there were also some victims brought in from the Netherlands, France and Germany. I found it strange, and somehow disturbing, that the memorial stones were almost all for the Dutch victims, often laid by the descendants of the deceased. Some came from Arnhem, close to where my father grew up. Others had the same first name as my father, Gerrit. These coincidences, by creating a feeling of a linkI wondered whether it was partly because so many Dutch Jews managed to survive the war to remember their dead relatives; perhaps there were so few stones for Polish victims because so few of them had any surviving descendants to come lay stones for them. Or perhaps the post-WWII historical narrative of the Soviet bloc, in which Soviet, and especially Russian, victims of the Nazis were paramount, left little time or inclination to consider the Jewish victims of the Nazis. I don't know, but something about it left me feeling uneasy.

As I took photographs of the overgrown, unused railway siding that once led to the camp, a busload of young Israelis, some wrapped in the Israeli flag, came out of the site singing. They seemed to be on a Holocaust memorial tour, and it must have been even more emotional for them than for me to see this site of mass death, in which an estimated 250,000 people were killed. Sobibor is also little known in the West, again partly perhaps it was so deadly efficient; only about 50 people are known to have survived, most of whom escaped in the prisoner revolt in October 1943 that damaged the facility and led to it being closed.

By pure coincidence, a few days earlier I had stayed in a hotel with satellite TV and had watched a History Channel documentary about Simon Wiesenthal. One of his most notable successes in tracking down war criminals was his location of the commander of Sobibor (and later Treblinka), Franz Stangl, in Sao Paolo in 1967. Stangl was arrested, extradited to West Germany and tried for war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison, which amounted to six months, as he died of a heart attack in 1970. Much of what we know about Sobibor came to light during this trial.

It was a shock, after all this grim recollection of death and destruction, to ride 10 kilometres through the forbidding forest and emerge at a lake south of Wlodawa (Okuninka) where thousands of people were enjoying a summer afternoon at the lake. Restaurants, fun fairs, bars and shops were packed. Life moves on, even at the site of profound tragedy.

The ride through Belarus, still along the rail lines of pre-WWII Poland, had fewer overt reminders of the Holocaust, although plenty of WWII. Belarus bore the brunt of fighting on the Eastern Front, with around a third of its population dying between 1941 and 1944. There are memorials everywhere to the Red Army, still faithfully tended with fresh wreaths, and memorials to the partisans who fought the Germans from the forests. However, the Jews of modern-day western Belarus (which was part of Poland occupied by the Russians) suffered horribly in the war years, most of them summarily executed in 1941, immediately after the German invasion, shot in forests and buried in mass graves by the SS and locally recruited death squads.

Arriving here in Vilnius, dubbed the Jerusalem of the North by Napoleon, there are more remembrances of the Holocaust. Vilnius had 140,000 Jewish citizens in 1940, and there were some 200,000 in the country as a whole. Fewer than 10,000 would survive the war. I went to the Lithuanian national holocaust memorial museum, a moving tribute to the destruction of an entire community and way of life. On my way out of town tomorrow, riding toward the coast, I will pass Pareniai, where so many Vilnius Jews were executed in pits dug outside the city.

This section of the bike trip has taught me a lot I didn't know about what happened in WWII in eastern Europe, something that is often passed over lightly in our Western history books. It has also left me saddened, thinking of how often this sort of wholesale destruction of a people has been attempted over the centuries (the North American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, Rwanda's Tutsis, the Armenians of eastern Anatolia, entire city-states in Central Asia during the Mongol onslaught, to name but a few cases). I wonder whether, as Earth's population continues to skyrocket and as more and more people aspire to a Western standard of living, putting increasing strains on land, water, food, forests, oceans, whether we will see a resurgence of this sort of lebensraum idea and killing and mass deportation to achieve it. Today war criminals get sent to the Hague; perhaps in 50 years they will be given medals by their countries instead.

Postscript, Kaunas, August 7

As I took photographs of the overgrown, unused railway siding that once led to the camp, a busload of young Israelis, some wrapped in the Israeli flag, came out of the site singing. They seemed to be on a Holocaust memorial tour, and it must have been even more emotional for them than for me to see this site of mass death, in which an estimated 250,000 people were killed. Sobibor is also little known in the West, again partly perhaps it was so deadly efficient; only about 50 people are known to have survived, most of whom escaped in the prisoner revolt in October 1943 that damaged the facility and led to it being closed.

By pure coincidence, a few days earlier I had stayed in a hotel with satellite TV and had watched a History Channel documentary about Simon Wiesenthal. One of his most notable successes in tracking down war criminals was his location of the commander of Sobibor (and later Treblinka), Franz Stangl, in Sao Paolo in 1967. Stangl was arrested, extradited to West Germany and tried for war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison, which amounted to six months, as he died of a heart attack in 1970. Much of what we know about Sobibor came to light during this trial.

It was a shock, after all this grim recollection of death and destruction, to ride 10 kilometres through the forbidding forest and emerge at a lake south of Wlodawa (Okuninka) where thousands of people were enjoying a summer afternoon at the lake. Restaurants, fun fairs, bars and shops were packed. Life moves on, even at the site of profound tragedy.

The ride through Belarus, still along the rail lines of pre-WWII Poland, had fewer overt reminders of the Holocaust, although plenty of WWII. Belarus bore the brunt of fighting on the Eastern Front, with around a third of its population dying between 1941 and 1944. There are memorials everywhere to the Red Army, still faithfully tended with fresh wreaths, and memorials to the partisans who fought the Germans from the forests. However, the Jews of modern-day western Belarus (which was part of Poland occupied by the Russians) suffered horribly in the war years, most of them summarily executed in 1941, immediately after the German invasion, shot in forests and buried in mass graves by the SS and locally recruited death squads.

Arriving here in Vilnius, dubbed the Jerusalem of the North by Napoleon, there are more remembrances of the Holocaust. Vilnius had 140,000 Jewish citizens in 1940, and there were some 200,000 in the country as a whole. Fewer than 10,000 would survive the war. I went to the Lithuanian national holocaust memorial museum, a moving tribute to the destruction of an entire community and way of life. On my way out of town tomorrow, riding toward the coast, I will pass Pareniai, where so many Vilnius Jews were executed in pits dug outside the city.

This section of the bike trip has taught me a lot I didn't know about what happened in WWII in eastern Europe, something that is often passed over lightly in our Western history books. It has also left me saddened, thinking of how often this sort of wholesale destruction of a people has been attempted over the centuries (the North American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, Rwanda's Tutsis, the Armenians of eastern Anatolia, entire city-states in Central Asia during the Mongol onslaught, to name but a few cases). I wonder whether, as Earth's population continues to skyrocket and as more and more people aspire to a Western standard of living, putting increasing strains on land, water, food, forests, oceans, whether we will see a resurgence of this sort of lebensraum idea and killing and mass deportation to achieve it. Today war criminals get sent to the Hague; perhaps in 50 years they will be given medals by their countries instead.

Postscript, Kaunas, August 7

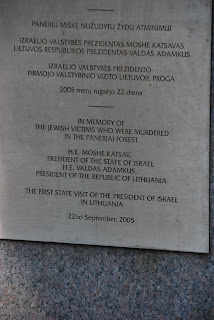

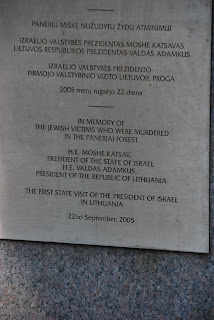

On my way out of Vilnius two days ago, I stopped in the forest of Paneriai, the principal site of executions of Lithuanian Jews from 1941 to 1944. As in much of the territory conquered by the Germans in 1941, from the very first days of the invasion, there were mass killings of local Jewish citizens. At first, the Germans stirred up local nationalists, angered by 2 years of Soviet oppression, by equating Jews to the hated Communists, and there were a number of unorganized killings by Lithuanian militias. Quite soon, however, the Germans organized matters and had the Lithuanian police battalions carry out their dirty work. Nearly 100,000 people were murdered in Paneriai, and most of them were subsequently dug up, burned and then the ashes reburied. I had the forest to myself in the early morning, and walking around the various Soviet and post-Soviet memorials was very moving.

On my way out of Vilnius two days ago, I stopped in the forest of Paneriai, the principal site of executions of Lithuanian Jews from 1941 to 1944. As in much of the territory conquered by the Germans in 1941, from the very first days of the invasion, there were mass killings of local Jewish citizens. At first, the Germans stirred up local nationalists, angered by 2 years of Soviet oppression, by equating Jews to the hated Communists, and there were a number of unorganized killings by Lithuanian militias. Quite soon, however, the Germans organized matters and had the Lithuanian police battalions carry out their dirty work. Nearly 100,000 people were murdered in Paneriai, and most of them were subsequently dug up, burned and then the ashes reburied. I had the forest to myself in the early morning, and walking around the various Soviet and post-Soviet memorials was very moving.

No comments:

Post a Comment